I was involved in an interesting conversation about collecting last week while at an NHL game in Ottawa.

There was a group of us who had taken more than a few trips around the sun, or were on the back nine, or whatever you want to say about old guys talking about hockey and hockey cards.

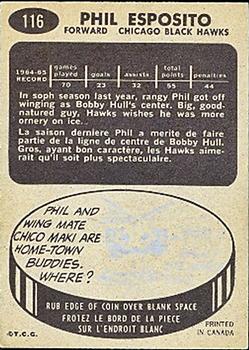

One of them had mentioned that he heard on the pre-game show that it was recently the 60th anniversary of Phil Esposito’s first NHL game. Esposito also celebrated his 82nd birthday on Tuesday.

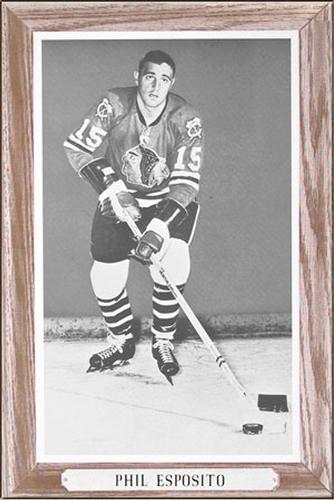

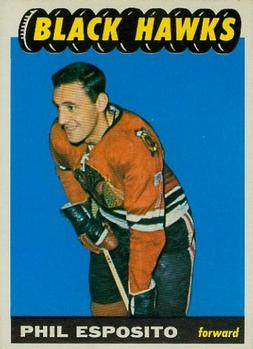

I was the youngest of the group, and I did not start collecting until the age of five in 1969. The other guys were five to ten years older, which in the hobby can be an eternity. They were around for Esposito’s first BeeHive photo and his rookie card that was made when he played for the Chicago Blackhawks. They grew up in the Original Six era while I was only three when the league doubled in size to 12 teams for the 1967-68 season.

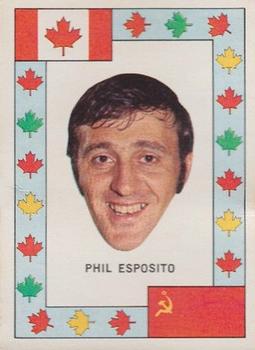

Over my years in the industry, I have been lucky enough to meet Esposito a few times, including at the Expo in Toronto, at NHL All-Star events, and at an Upper Deck function when he was signing memorabilia for Upper Deck Authenticated. I have a wall in my basement dedicated to the 1972 Canada-Soviet Summit Series, and a UDA autographed Esposito 8×10 autographed photo is an important part of my display.

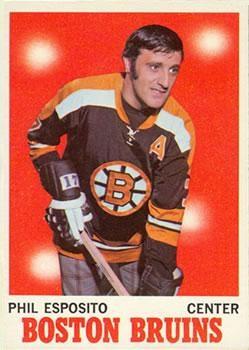

I was telling the other guys that Esposito hated posing for photos. It didn’t matter whether they were for BeeHive photos or Topps cards or O-Pee-Chee cards or for the team’s media department, he just didn’t like the tedious obligation of “posing” for photos.

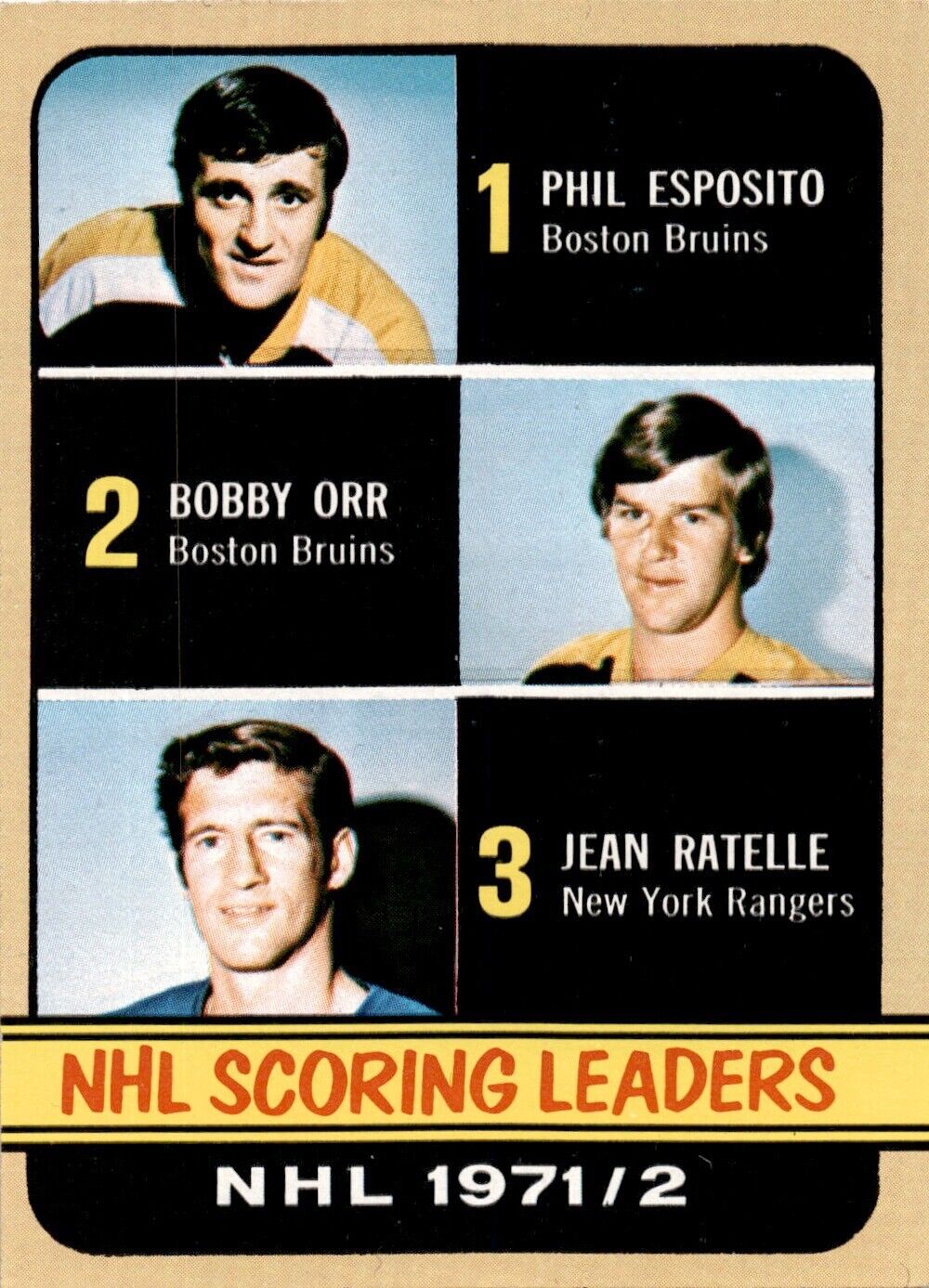

In fact, if you look closely at his 1970-71 O-Pee-Chee and Topps cards, you will notice that while the rest of the Bruins are in uniform for their photos, Esposito is wearing checkered dress pants. He threw on a Bruins sweater with no elbow pads or shoulder pads underneath, took his pose, forced a smile, and his day was done. It’s a bit of hobby lore you can own for a pretty modest price.

Then the quasi-debate started with a question. Actually, there were three or four questions. They looked at me thinking I knew everything about cards, so I must know the answer.

But it has always puzzled me too.

“Why is my Phil Esposito rookie card a Topps card and not an O-Pee-Chee card?”

There is a grey area to that question. It has slipped through the hobby publication and price guide’s five-hole the way that Esposito used to poke rebounds through a goalie’s legs.

More questions followed. Some about Phil. Some about his late brother, Tony.

“Why did Phil Esposito not have a rookie card until the 1965-66 set?”

“Why did Tony Esposito not have a card with the Montreal Canadiens before he was traded to the Chicago Blackhawks?”

Parkhurst, Topps and O-Pee-Chee

For the first half of the 1960s, the NHL had two licensed trading card companies. The six-team league was split in half for collectors. Parkhurst got the Montreal Canadiens, Toronto Maple Leafs and Detroit Red Wings. Topps got the New York Rangers, Boston Bruins and Chicago Blackhawks.

It seems like an unfair balance between the two companies. Montreal and Toronto were the two strongest and most popular teams in the NHL at that time. Detroit was coming off a dynasty driven by the greatest player in the league, Gordie Howe.

Topps had Boston and the New York Rangers, who were popular in their markets but were not contenders. The Blackhawks had won a Stanley Cup early in the decade and had young superstar Bobby Hull, as well as other popular Blackhawks like Glenn Hall and Stan Mikita.

In Canada, Parkhurst cards were more popular than Topps cards simply because of the three teams they had, but the Canadian market was still strong for Topps.

It was also tough to produce a full set of cards with only three teams. Topps included a subset of retired NHL greats in their sets. Parkhurst, meanwhile, included two cards of the Montreal and Toronto players and coaches and one each for the Detroit players and coaches.

Here is where it gets tricky.

Even though the Topps are branded as Topps, they were printed in Canada by O-Pee-Chee, a candy manufacturer in London, Ontario that had a licensing and distribution agreement with Topps. For some reason, however, the cards were not branded as O-Pee-Chee until the 1968-69 season, when there was a 216-card O-Pee-Chee set and a 132-card Topps set. The sets had the same designs, and the same photo was used for 132 players who appeared in both sets. The fine print on the Topps cards had T.G.C. in one bottom corner (Topps Gum Company), and Printed in Canada on the other bottom corner.

The card backs had similar designs, but the O-Pee-Chee cards had English and French backs while the Topps cards were in English. Topps cards were bilingual when O-Pee-Chee printed them. The card numbering for the sets was also different, as the sets were different sizes.

When I was the editor of Canadian Sportscard Collector magazine in the early 1990s, we referred to the cards through 1968 as Topps, while in Canada they were sometimes referred to as Topps Canada. Some collectors refer to those eras as O-Pee-Chee cards, such as the book on O-Pee-Chee cards written by Richard Scott, who is also a Canadian Sportscard Collector alum.

Parkhurst stopped making cards before the 1964-65 season, meaning that Topps could include all six teams. Like their NFL set of 1965, Topps produced “tallboy” cards, which were 4 11/16” tall instead of 3 1/2 “ tall. Esposito, we determined, should have had his rookie card in this set. After he had 80 points in 43 games with the St. Louis Braves of the Central Hockey League, he was called up to play 27 games for the Blackhawks. He had a very unEspo-like three goals and two assists for five points. It was his only season below 20 goals until his final season in 1980-81 with the New York Rangers.

Points Machine

In his first full season in Chicago, Esposito had 23 goals and 32 assists for 55 points in 70 games. It was his first of three very productive years for the Blackhawks before they traded him to Boston.

Playing with Bobby Orr, Esposito became hockey’s most prolific goal scorer, putting up numbers that Gordie Howe, Rocket Richard and Bobby Hull could never match. In his eight seasons with the Bruins, he scored 50 or more goals five times, he scored 60 or more four times, and he netted 76 goals in 78 games in the 1970-71 season. He also helped the Bruins win two Stanley Cups.

I remember him saying what it was like playing with Bobby Orr. He tried to anticipate where Orr was going to take the puck and where he would go where Orr would find him. Orr, he said, was like a great quarterback or point guard on the ice.

He spent the last five years of his career with the New York Rangers and continued to score 34 or more goals every year. He never wanted to go the Rangers, Boston’s biggest rival. He did not ask for a no-trade clause in his contract because he trusted Harry Sinden on his word when he told Esposito he would never be traded. He was sent to New York and led the Rangers to a Cup final. Despite putting up big numbers, it was obvious that the passion that burned in Boston was not quite the same in New York.

The consensus among the group was that Esposito is probably the most undervalued player of his era in the hockey card market. It was also unanimous that had he remained in Boston, he would have scored more than 800 goals instead of retiring at 717. In his mid and late 30s, despite playing on Rangers teams that were not deep in talent, Esposito remained a scoring machine. If you compare his scoring numbers with Wayne Gretzky’s numbers toward the end of both careers, they are not close.

We didn’t even mention how Esposito put the entire country of Canada on his back and became the emotional leader in the 1972 Summit Series.

Tony O on Cards: Better Late Than Never

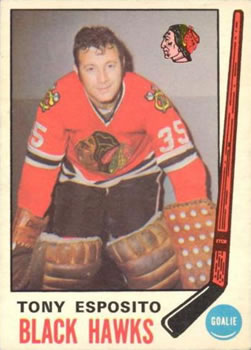

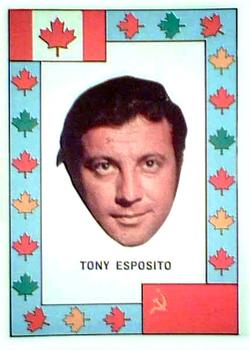

When the discussion switched to Tony Esposito, the question was why did he not have a card until 1969-70 when he played for the Blackhawks. That one was a little easier.

Tony Esposito did, in fact, begin his career with the Montreal Canadiens. He appeared in 13 games with the Habs, but was buried in the depth chart behind Rogie Vachon and Gump Worsley The Canadiens were also waiting on Ken Dryden to graduate from Cornell and join the team. O-Pee-Chee did not have room for three Montreal goalies in their sets.

Few collectors know that Tony Esposito actually did win a Stanley Cup. With Worsley injured, he backed up Vachon and dressed for the 1968-69 Stanley Cup finals, though he did not see any action. If the value for the 1969-70 Tony Esposito card seems low to you, there is also a reason for that.

It was double printed.

On the printing form used by O-Pee-Chee for the second series, some of the players were put on the form twice to fill out the blank spaces.

After the season, he was left unprotected and was claimed by Chicago on waivers. He joined the Blackhawks in 1969-70 and immediately became the starter. In his second year there, the year of his rookie card, he led the Hawks to the Stanley Cup finals, where they lost to Dryden and the Canadiens. In 1972, Dryden and Esposito would share the goaltending duties for Team Canada in the Summit Series against the Soviet Union. Esposito won the Calder Trophy as the NHL Rookie of the Year in 1969-70, while Dryden won it in 1971-72, the year after he won his first of six Stanley Cups with the Canadiens.

In 1998, the Hockey News released its list of the top 100 NHL players of all time. Phil Esposito ranked 18th, while Tony Esposito ranked 79th. Tony, the group agreed, was more collectible in the hobby, though we all agreed that Phil should be.

Hockey’s Best Bros

The last question we debated was who was the most collectible brother combination in hockey card history. Were there any brothers more collectible than the Espositos? The first brother combination to compare was the Richard brothers.

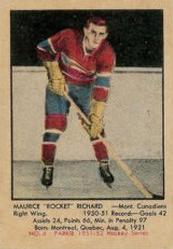

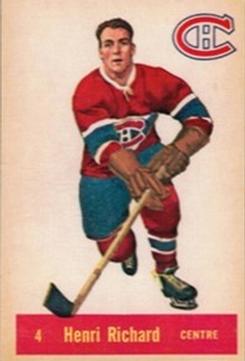

Maurice Richard began his career in 1942 did not get a rookie card until the 1951-52 Parkhurst set. Henri’s rookie card was in the 1957-58 Parkhurst set.

Maurice Richard was the first player to score 50 goals in a season and the first to score 500 career goals. He was an eight-time Stanley Cup winner, and eight-time First Team All-Star and a six-time Second Team All-Star. Henri is the all-time leader with 11 Stanley Cups as a player. He played for 20 seasons and retired with 1,046.

While Henri Richard’s legacy is his longevity and being a leader and a complete player, the debate takes us back to the 1970-71 Stanley Cup final between Chicago and Montreal. In Game 7, it was Henri Richard who scored the tying goal and then the Stanley Cup-winning goal on his former teammate, Tony Esposito.

We never solved the argument of which brother combination was better, as there were solid points on both sides. There have been many other brother combinations through the years. Bobby Hull and Dennis Hull are in the conversation. Bryan and Dennis Hextall are a solid combination. Ken Dryden and Dave Dryden were the first brothers to face each other as starting goaltenders. Pavel and Valeri Bure were popular during the sports card explosion in the early 1990s. And some brother combinations, like the Sutters, the Plagers and the Staals, have more than two. The only thing we did determine, however, was that among the four players, Phil Esposito was the most underrated, and Tony Esposito was the only player who was never on a BeeHive photo and whose rookie card is an O-Pee-Chee.

So Happy Birthday Phil. I hope you don’t have to sit through a photo shoot.